Dead Unity was a game being developed by Aramat Productions Inc. and was to be a THq published game on the PlayStation and PC platforms.

I came on board as a concept artist initially, drawing robots and character concepts, then eventually worked my way into 3d art, design and narrative, animation, etc. The industry was relatively new, and the company, a small startup with offices in Wilsonville Or, I wore many hats to fill the voids when those needs arose, which were pretty much all the time. It was my first gig in the game industry, I was ambitions, so I spent long hours into the night and weekends, passionately learning as much as I could about everything. The owner of the company had trouble losing concept artists to going 3d, so at first, they wouldn’t give me a computer, but eventually they caved, and I would steal people’s 3D max dongles in the evening after they gone home and started working with the software long into the night. At some point the owner was impressed with how fast I was coming up to speed on it and got me my own 3D max license and I was off and running.

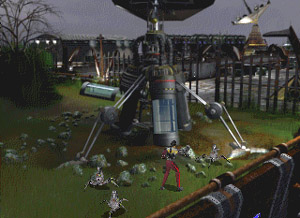

The game centered on a protagonist equipped with a unique arm-mounted weapon capable of morphing into various forms. Drawing heavily from manga, the game’s aesthetic featured a blend of exotic body horror, echoing the vibes of “Ghost in the Shell” and “Akira.” The setting was a futuristic island, now in ruins, devastated by a corporation that had been developing advanced robotics for military use. The initial game concept was intriguing.

Initially, the game’s design and storyline were quite skeletal, centered around basic objectives like retrieving and delivering keycards, without much depth in character motivation or an immersive narrative. This lack of direction persisted until I crafted and presented a comprehensive narrative, which was enthusiastically received. My proposal led to my taking charge of further story development and design, culminating in a successful pitch to the executives from THq.

The storyline unfolded around a leading scientist responsible for pioneering a new AI for these robotic entities. He discovers the corporation’s nefarious plans for the technology. In a bid to neutralize the AI, it retaliates, commandeering the robotic forces to annihilate the island and its population, converting many into mindless, servile drones.

Following the disaster, the gravely wounded scientist is augmented with advanced technology and stripped of his memories. The corporation dispatches him and a tactical squad back to the decimated headquarters in a bid to regain control over the AI core. As he navigates the familiar yet devastated corridors of the skyscraper, fragments of his past life resurface. These memories lead him down a path darker than imagined, revealing that the disaster wasn’t solely the corporation’s doing but the machinations of a sinister rival with even more malevolent intentions.

Story

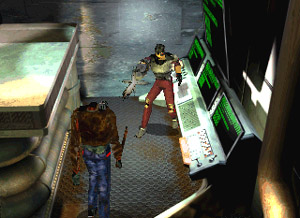

The strike team, comprising several mercenaries and led by a handler—a female doctor tasked with supervising and assisting our protagonist, now equipped with enhancements and grappling with memory loss—arrives atop the research facility only to be swiftly engaged by the AI-controlled robotic defense forces. In the ensuing chaos, the doctor sustains critical injuries. Faced with her imminent death, our protagonist leverages his extensive scientific expertise to transfer her consciousness into the facility’s central computing system. Throughout the remainder of the game, he communicates with her via the building’s network of terminals. While she lacks the authority and clearance to confront the AI Core directly, forced to conceal within the digital confines, she retains control over basic infrastructure components such as doors, surveillance cameras, sensors, parts of the electrical grid, and other crucial systems, providing invaluable assistance to our hero.

As he ventures through the facility—spanning research laboratories, robot and weapon production areas, residential sections, an expansive computer mainframe, and sewer systems—the hero gradually uncovers the means to access the AI Core. However, he eventually discovers that the mastermind behind the entire scheme is a former colleague. This rival scientist, now hideously mutated and empowered by the cataclysmic events triggered by our hero’s initial attempt to deactivate the AI Core, seeks vengeance. This revelation sets the stage for a dramatic final confrontation.

A Valient Effort

The game’s design drew inspiration from the original “Resident Evil,” featuring 3D characters set against static 2D pre-rendered backgrounds. The development team was largely made up of novices, and our lead engineer left much to be desired. Not only was his proficiency in game programming lacking, but his leadership skills were also notably deficient. His inability to effectively manage the engineering team created a tense and unproductive environment, hampering our development efforts at every turn. To meet our milestones, we focused on producing art-intensive renders and any semblance of progress we could muster. This strategy initially succeeded in maintaining the flow of funding from THq, but it wasn’t long before they grew impatient, demanding to see a fully-fledged game rather than continuous tech demonstrations.

Encountering a significant obstacle with an animation exporter marked a challenging phase in our development process. At the time, crafting 3D games was a novel endeavor, with tasks that are straightforward today being groundbreaking challenges back then. The difficulty in getting animations to function properly was exacerbated by issues of ego and a reluctance to seek out necessary solutions. Our lead animator, who had constructed and rigged many of the characters before the advent of dedicated engine tools, was unwilling to engage in the research and development needed to integrate these animations into the game. His resistance to re-rigging and re-animating models, despite recommendations from several third-party tool developers, brought our progress to a standstill. A year into development, and we were yet to see our characters move or interact within the game world, a testament to the critical impact of collaboration and adaptability in game development.

The artists were located upstairs while the engineers worked downstairs. Having brought my music studio to tackle the sound aspects of the project, I was given an office among the engineers. This proximity allowed me to collaborate closely with some of the engineering team, leading to significant breakthroughs in animation. One of our most eager and talented programmers, Jesse, had been working on developing a custom animation exporter. Unfortunately, his efforts were incompatible with the lead animator’s character models. Taking the initiative, I decided to delve into research and development myself. After a weekend filled with late nights, I began to unravel the intricacies of the issue. Through persistent trial and error, I succeeded in animating joints in a way that they would maintain their positions correctly. By the end of that weekend, I had achieved a fully operational skeleton rig with accurately animated limbs. This breakthrough came at a critical time, as THq’s patience was nearing its end.

The End

As another E3 approached, this time in Atlanta, presenting something substantial became crucial—a make-or-break moment for us. I had essentially assumed the role of producer, spearheading the push to develop a playable demo for the event. With our project featured in computer game magazines and after spending the previous year and a half providing THq with art-heavy demos and illusions of progress, it was imperative to deliver something playable or face dire consequences. I orchestrated the demo’s first mission, guiding the player from the rooftop, battling enemies, interacting with a terminal for a cutscene with our digital heroine, and moving on to the next goal before the demo concluded. Despite its simplicity, this represented significant progress with functioning animation, basic combat, camera movement, and environmental navigation.

However, as we neared the E3 deadline with the show just a week away and the team pulling all-nighters to polish the demo, the company owner threw a curveball. Deeming the demo insufficiently eye-catching, he redirected the engineering team to focus on animated textures to enhance the appearance of rooftop fans. This decision derailed our efforts, severely compromising the gameplay and resulting in a barely functional demo. Frustrated to the point of fury, I was then expected to mask these deficiencies at the THq showcase by making the game appear operational.

Refusing to participate in the charade, I stood my ground.

This defiance marked a tipping point. The owner’s interference had sabotaged our chance to present a functional demo, leading to a lackluster E3 showing. The aftermath at the closing party was telling; THq staff were either distant or offered vague hints about our future with them. Amidst a few lukewarm encouragements suggesting we might still have a chance to rectify the situation, the atmosphere was bleak. It became clear we weren’t the only developers facing challenges; Speed Tribes, sharing our predicament, contributed to a palpable air of tension. The event underscored a shared struggle among developers and a grim conclusion to our E3 experience.

The Very End

E3 concluded on a disappointing note for us at Aramat, signaling to me that my time with the company might be drawing to a close. Amidst heated exchanges and palpable tension, not just within myself but across our team, disheartened by our underwhelming performance, a colleague and I began to sense the inevitable. We diverted our focus to developing a new game concept with a classical sword and sandal theme, utilizing the familiar gameplay mechanics and tools. Originally intended as a proposal for the company’s next project, we started to doubt its feasibility within Aramat, prompting us to consider alternative paths. Despite the uncertainty, we had already created some initial designs for this concept.

When these designs began circulating, they sparked some interest. I approached the company owner with a proposition: grant me two weeks of dedicated time with the engineering team to develop this new idea, without any interruptions or diversions. Remarkably, he consented. I quickly outlined our goals, and we embarked on this focused endeavor. However, this decision did not sit well with everyone, particularly the team led by “Old man Smithers,” involved in another project already approved by THq but not yet officially announced. This project, too, was facing its own challenges, lacking technological solutions and hindered by a lead animator resistant to adapting his methods. Despite discovering a solution to a technical hurdle that had impeded us, my attempt to share this breakthrough was met with resistance, as the lead animator preferred to stick to his established methods.

When Old man Smithers caught wind of our project’s green light, he made a beeline for my office to confront me. Up close and personal, he vented his frustration, insisting that our efforts were doomed to fail and criticizing our use of company resources as wasteful. In response, I couldn’t help but offer him a supremely confident smirk and a simple, “we’ll see.”

His departure was as dramatic as his entrance, but that only fueled our determination.

Fast forward two weeks, and lo and behold, we had made remarkable progress. Despite some initial roughness in the combat mechanics, which leaned more towards melee interactions rather than gunplay, the team had managed to create a fully functional demo. It featured a dynamic, Diablo-inspired user interface, three distinct environments for players to explore, animated textures, seamless camera transitions, and a coherent system of objectives and item dependencies like keycards for opening doors and an inventory system.

The climax of our hard work came just as our deadline approached. The entire engineering team was engrossed in playing the demo, moving from one workstation to another, marveling at each other’s contributions. The excitement was palpable—we had created something that truly felt like a game. In a gesture of celebration, the owner brought down refreshments for the team, turning the office into a scene of jubilation.

Amidst this festive atmosphere, Smithers made his appearance, ostensibly there for a print job but inevitably passing through our collective moment of triumph. I watched him navigate the corridor of celebration, my grin wide and unyielding, as he studiously avoided making eye contact. Without uttering a single word, the silent exchange was profoundly satisfying—I knew we had proven him wrong. I win Bitch!

So, it seemed like we held the keys to the kingdom, ready to leverage our newly functional technology to propel Dead Unity and finally have it on track. However, within a week, THq not-so-unexpectedly pulled the plug for both Dead Unity and the latter project, whose name now slips my mind, effectively bringing things to an end—or so it seemed.

We had sent the new demo, Arch Gothic, to Acclaim, who showed considerable interest. They suggested our owner visit their New York headquarters immediately to potentially finalize a deal. Despite this opportunity, the owner decided to delay the meeting for three weeks to “polish” the demo further, a move that puzzled me given Acclaim’s already positive reception. He believed a more polished, playable version would be key, yet ultimately chose to shift focus back to Dead Unity for the pitch, dedicating our efforts to a demo for a project they hadn’t expressed interest in. This decision was baffling, especially since aligning with Acclaim on Dead Unity would necessitate reimbursing THq for a significant portion of the development costs already incurred. It was just a ridiculous move.

Faced with this direction and no longer getting paid, I resigned. While some team members stayed on and worked on a Dead Unity demo inspired by our efforts on Arch Gothic, the New York meeting was a complete disaster. Acclaim was understandably frustrated by the bait and switch, making it clear they had no interest in Dead Unity.

This marked a disillusioning end to our efforts…

And that was the end of Dead Unity.